Britain’s interior minister has been forced to deny the government’s new crackdown on migrant boats crossing the Channel was announced in language “not dissimilar to that used by Germany in the 30s”.

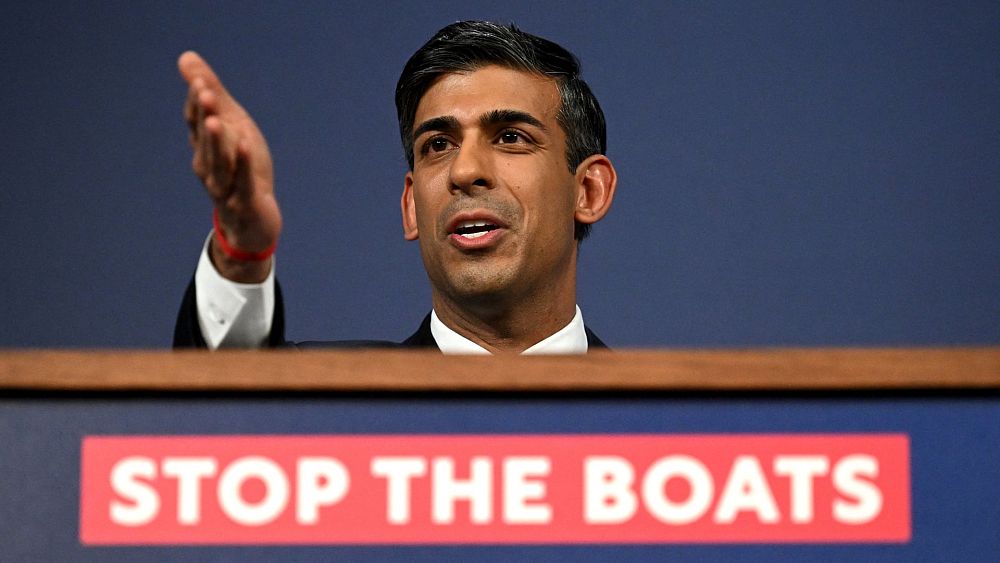

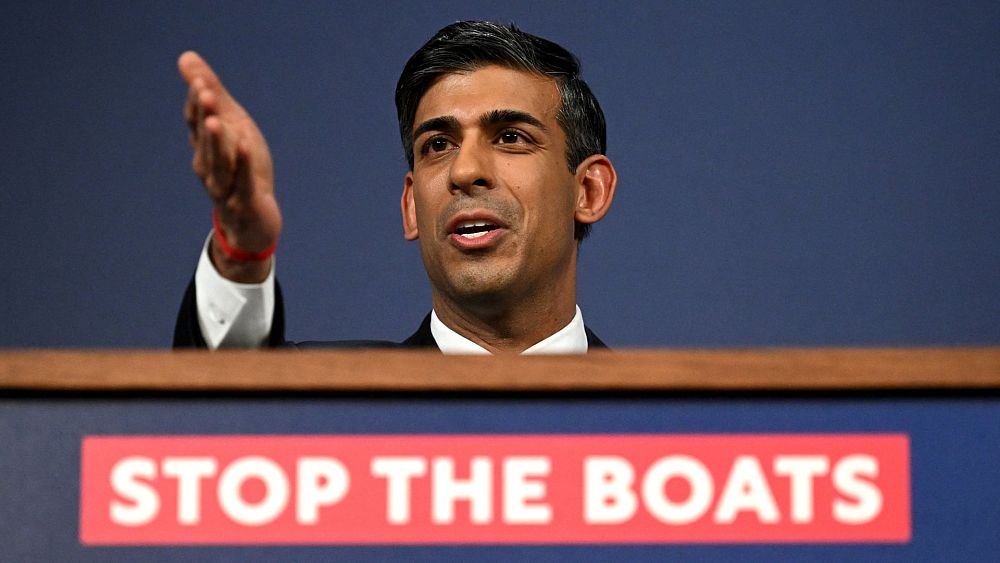

Home Secretary Suella Braverman did a round of media interviews on Wednesday and faced a barage of questions from journalists about the new Illegal Migration Bill which saw her pledge to “stop the boats”.

“Last year over 45,000 people made the unsafe, unnecessary and illegal journey across the Channel,” Braverman said, announcing the new policy.

“Our asylum system has been overwhelmed. We’re now spending almost £7 million (€7.86 million) a day on hotels. Stopping the boats is one of the five promises the Prime Minister has made to the British people. And it’s my top priority. That’s why today I’m announcing a new Illegal Migration Bill to do exactly that.”

She was asked about a tweet by former England football star turned BBC pundit, Gary Lineker, who called the new legislation “immeasurably cruel” and likened the language to that of Germany in the 1930s.

Braverman said she was “disappointed” by Lineker’s comments, and claimed to be “on the side of the British people” by introducing the new legislation.

Anglo-French summit coming up this week

The latest UK push to stop people coming to the UK across the Channel from France and claiming asylum — which the United Nations’ Refugee Agency says it is “profoundly concerned” about — comes just days ahead of a planned Franco-British summit on 10 March.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak will be in the French capital and the meeting with Emmanuel Macron, at the first such summit since 2018, is being billed as “an opportunity for the two leaders to deepen cooperation in a range of areas, including security, climate and energy, the economy, migration, youth and foreign policy”.

The French government has offered no official reaction to the provisions outlined for dealing with migrants in the new legislation, but Jonathan Portes, a senior fellow at UK in a Changing Europe says the French haven’t seen anything yet to get prickly about.

“What the French get upset about is when the UK Government says ‘this is all the fault of the French, if they just got a grip of their own borders and what’s happening there then none of this would be happening’,” explains Portes, whose group is a network of academics whose aim is to promote independent research into the “complex and ever-changing relationship between the UK and the EU”.

“Understandably, the French aren’t too happy about that. But there wasn’t any of that yesterday, it was all about what’s going to happen in the UK. So the French may have their views on whether this is essential or workable or moral or legal or whatever, but if I were a French government official I’d shrug my shoulders and say ‘well, the Brits are doing what the Brits are doing, in itself it doesn’t really affect us’,” he told Euronews.

‘We’re not breaking the law’

UK government ministers have insisted that the new legislation does not break the law — even as human rights group Amnesty International said there’s a conflict between the new bill and international laws which protect asylum seekers and refugees.

“We’re not breaking the law and no government representative has said that we’re breaking the law. In fact, we’ve made it very clear that we believe we’re in compliance with our international obligations,” said Braverman, when challenged on Wednesday.

Alexander Heeps, a senior solicitor at Glasgow law firm McGlashan MacKay, which specialises in immigration, asylum claims and human rights, echoed Amnesty’s concerns over the legality of the bill.

“Yesterday’s announcement to the House of Commons in respect of this bill once again shows how willing the government are to run roughshod over domestic law and the United Kingdom’s international obligations,” said Heeps.

“The disdain shown towards fundamental principles such as non-refoulement and the provisions of the Refugee Convention should not only worry those who are fleeing persecution from their countries, but also those who are presently in the asylum system and the wider public in general,” he told Euronews.

Heeps said that before Brexit, the UK would have been able to make requests of other EU countries to take back people who end up in the UK and claim asylum there, “but that is no longer possible,” he said.

“This solution seems very much like the UK Government are trying to close the stable door after the horse has bolted and what this bill proposes will only serve to damage relations between the UK and its continental neighbours and create more problems than it intends to solve,” he said.

Public opinion in the UK, said Jonathan Portes, has become “considerably more positive towards immigration overall” in the last few years, but added the public also wanted to see the issue of irregular crossings in small boats dealt with.

“So I think it’s clear what the government’s trying to do, which is trying to polarise opinion again and try and focus attention on irregular migration to distract from its broader economic and political problems.”